How does blood flow in a vein?

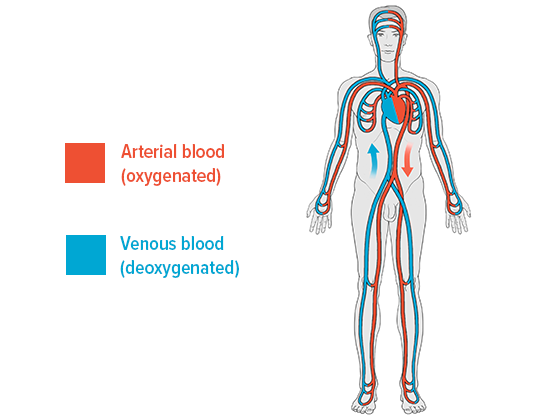

Blood is transported away from the heart when the heart beats. However, this pulse isn’t enough to carry the blood – once it has passed through the capillaries (tiny blood vessels) – through the veins as well. The heart is essentially a pressure pump rather than a suction pump. It only plays a minor part in the return leg of the cycle.

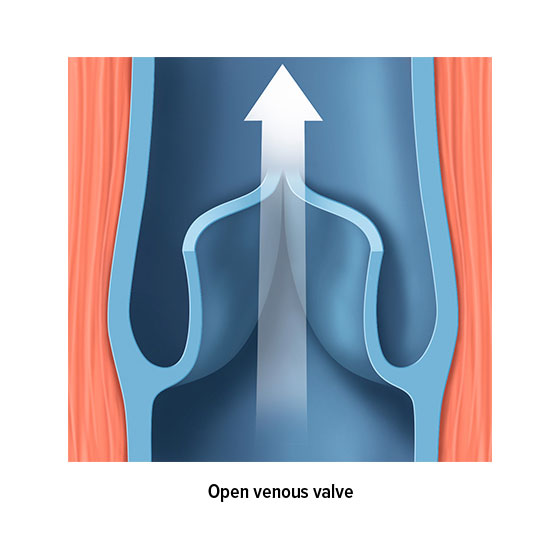

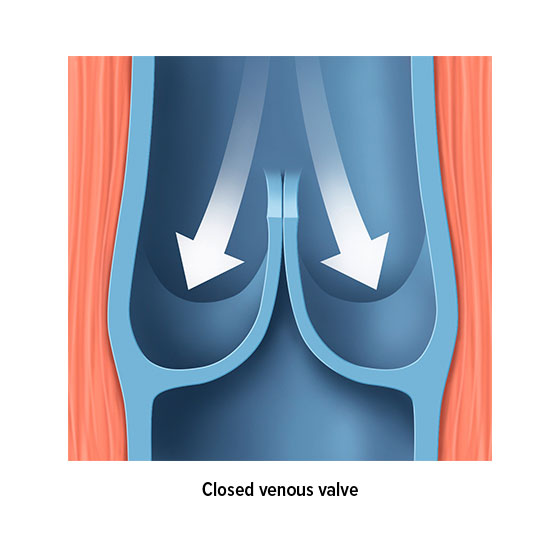

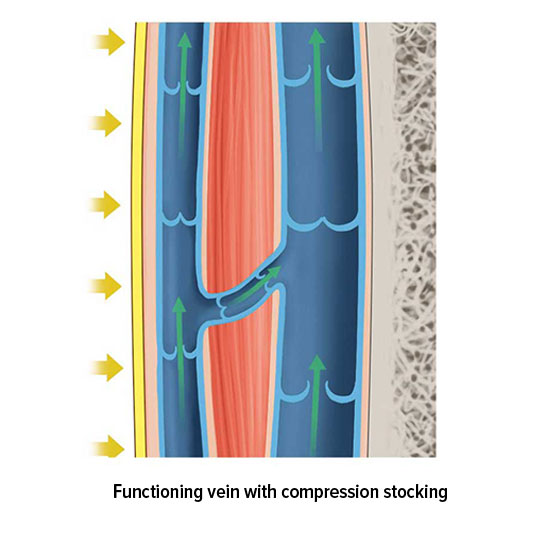

The venous valves are anatomically responsible for ensuring the blood flow. Most veins are divided into sections by valves. For example, there are up to 20 venous valves in the veins in our extremities, all of which work to ensure that our blood flows in the right direction – i.e. back to the heart. These valves function as a type of non-return valve. When pressure is applied to a section of vein, the valves open towards the heart and allow blood to pass along into the next section. However, the valves only open in one direction. This means that a healthy valve will prevent blood from flowing backwards.

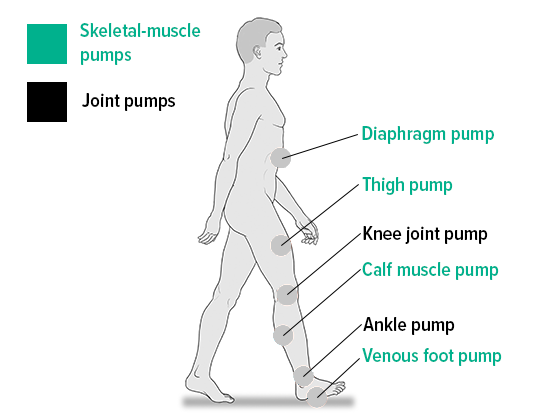

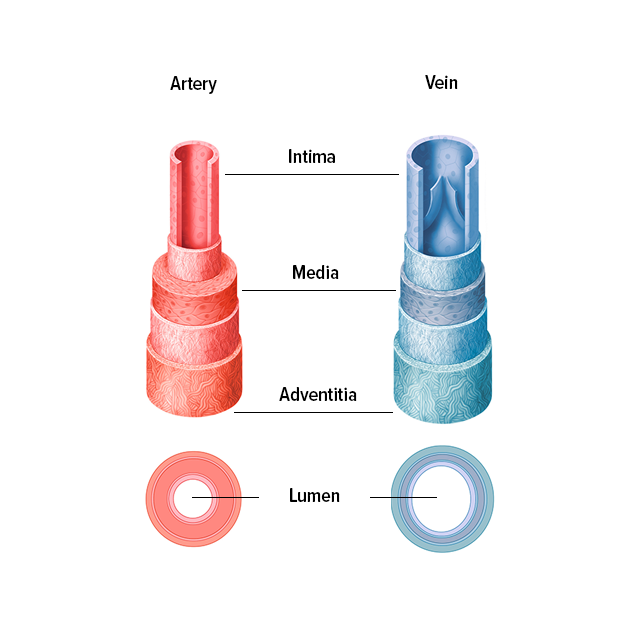

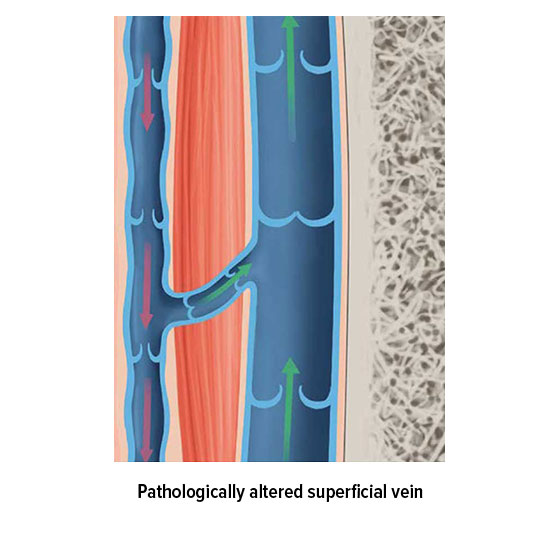

But how is pressure applied to the veins? Several mechanisms are responsible for ensuring that the blood flows back to the heart, and these are known collectively as venous pumps or skeletal-muscle pumps. When a muscle contracts, the vein closest to the muscle is also compressed, which allows the blood to continue on its journey back to the heart. The vessel wall acts as a counterpressure to the blood, and prevents the pressure in the vein from rising any further. When the muscle relaxes, the vein expands again. The resulting suction ensures that blood flows back from the deeper-lying sections of the vein and from the superficial veins closer to the skin into their deep-lying counterparts. Accompanying veins are compressed in a similar way, as the pulse passes through a nearby artery. Blood flow in the veins close to the heart is influenced by breathing, whereas blood flow in the abdomen is influenced by muscle contractions in the digestive tract.

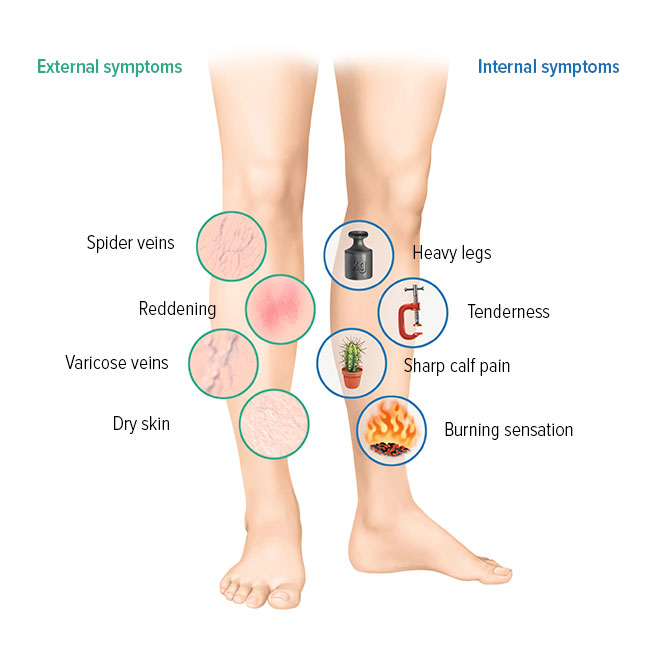

This interplay of compression and venous valves ensures that blood can be transported around the body despite gravity – and this happens 24 hours a day, throughout our lives. Small wonder, then, that the valves and walls of the veins often stop functioning correctly as you grow older, and that venous disorders arise